Photographer Interview: Albert Chong

See more photography by Albert Chong and friend him on Facebook.

D&B: Where are you from?

AC: I am originally from Kingston, Jamaica by way of Brooklyn, NY, San Diego, CA and presently Boulder, CO.

D&B: What kind of photography do you shoot and how did you get started – any “formal” training?

AC: My photography has been primarily focused on the use of the medium as a means of artistic and personal expression. My work has been a contributor to the discourses surrounding the contemporary visual arts of people of African and Asian descent. Inherent in these discourses are issues of race, identity, ethnicity, multiculturalism and postcolonial visual expression of methods of cultural retrieval.

My work has also investigated the role of family and ancestry in the constructed identity that is the artist. One of my better known body of work are the still life photographs that I construct sometimes using old family photographs, that in the context of the arrangement creates a shrine like tableaux that renders these Ancestors into Icons.

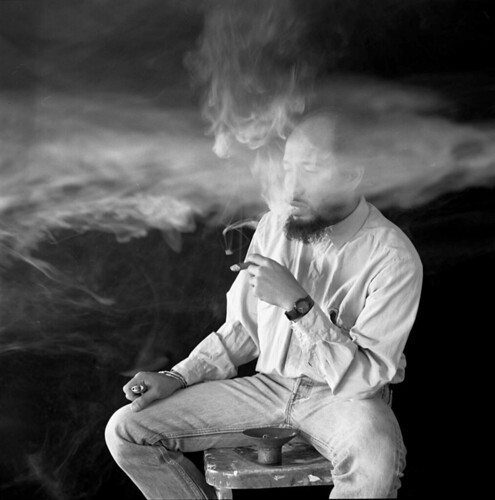

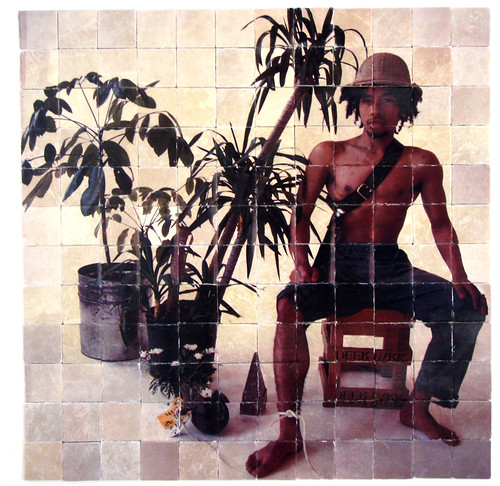

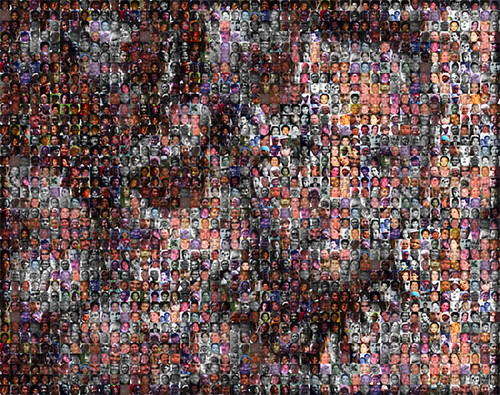

My work in fact spans many genres that include self-portraiture, Portraits, constructed images such as my Throne series, studies of the human form as in the ongoing series titled Projections, still-life, photo-mosaics on stone, an ongoing portrait project of artists and also of Jamaicans titled the Jamaican Portraits. I also work in other art mediums besides photography such as sculptural and kinetic installations. My work is primarily exhibited in museums nationally and internationally.

My interest in photography began as a teenager in high school in Kingston, Jamaica. It was while hanging out with some friends who were in the high school camera club that I first became exposed to the process of photography as I watched the print appear in the developer, I was hooked for life and my life was transformed by the realization of the almost limitless potential of this image-making process to realize and give form to the real and the imagined, to give visual utterances to those magnificent narratives that I could never hope to verbalize.

I was formally trained in photography in New York City. I attended the School of Visual Arts and graduated with a BFA with Honors. I also have a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of California, San Diego. I am also a Professor of Art, teaching photography at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

D&B: What cameras or techniques do you use?

AC: The range of cameras I use has declined dramatically with my shift to digital photography. I have a DSLR from 2006 that is a 12-mega-pixel camera – that is my serious camera, but the one I use the most is an Olympus point and shoot digital. It is my “go any where and shoot anything” camera, it even goes snorkeling with me around the world, it is waterproof to 33 feet, I am actually on my second version of this rugged camera, the last one got ruined by sand after I lost it in the surf in the Dominican Republic in 2010. I have been using these to make panoramas and a range of general uses.

Before the change to digital cameras, I still carried an Olympus point and shoot film camera, but that was my smallest camera, my single lens Reflex was a Nikon FM, my next format up was medium in which I worked with my beloved Hasseblad with a 50mm lens. I also had a fully decked out Bronica as well. The other camera, that is near and dear to me is an old Calumet monorail 4×5 view camera, a very tough and sturdy camera, that I have hauled to far off places as well, but that was used for much of my serious studio work including still lifes and portraits.

I used this camera frequently with type 55 Polaroid neg/pos film which is no longer available but which was a material for speeding up the creative process photographically. The discontinuance this film I believe to be one of the great losses to photography, so much great work was created with it and it was revolutionary in its design, by the simplification of the processing taking the darkroom out of the cycle greatly made the making and adjusting easier. It was never intended for use a primary recording substrate but as a way of insuring that your 4×5 Ektachrome sheet film would be perfect in exposure and lighting. I miss it.

D&B: Who are your mentors (in photography)?

AC: The majority of my mentors were not in photography, but I have had some incredible artists as teachers, including Faith Ringgold and the legendary Allan Kaprow, Italo Scanga and Newton Harrison. I did get great encouragement as an undergraduate student at the School of Visual Arts from teachers such as Bruce Bacon, Frances Mclaughlin Gill, Jan Groover.

D&B: Have you experienced any setbacks or different treatment along your photography career that you would attribute to being a woman and/or photographer of color? (this question is optional)

AC: Yes, I have had my share of racist discrimination, and I am fully aware that there are subtle methods and layers of exclusion that are designed to strain and filter out people whose difference was being from some demographic other than white, mainstream America. There were many instances in which I did not fit the prevailing notion among whites of what an artist looks like and that was generally white and male.

There was one incident that sticks out for me even after almost 30 years. I dropped off a portfolio of my photographs at a then very prestigious photography gallery called Light Gallery when I returned to retrieve it a few days later the gallerist was super enthusiastic about the work and mentioned that they were interested in giving the artist a show, she then asked me if I was the messenger and if I was would I relay this message to the artist. I then revealed that I was the artist and with her mouth agape in shock and surprise, the offer instantly evaporated.

There were many others including Aperture magazine in a meeting in 1992 the white man I met with I won’t mention his name told me they could not publish a book of my work because I was black and I was not famous and that their audience was primarily white. Well the irony there was that he was to become complicit in my fame when a traveling exhibition of photography my work was in hit New York and he was asked by the New York Times to review it and my photograph was used to advertise the show. At around the same time I was in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and my photograph was being used in the New York Times as well to advertise that one.

D&B: When did you realize you could have a career in photography? Describe your journey towards becoming a working photographer.

AC: In 1982, fresh out of art school I applied for and got a prestigious and highly competitive grant called the CAPS grant, it was for me, quite an achievement as every New York artist was applying for that grant and being awarded that grant gave me confidence both in my abilities to be an artist and the possibility of the arts providing the basis for a meaningful life.

I also had to be realistic and practical and with the very difficult acknowledgment that I may not become as successful as some of my contemporaries and that unlike them I would not be able to support myself much less a family with my art. That decision led me to get an MFA degree and take a teaching job in a university.

D&B: What do you hope to achieve with your photography?

AC: Like any artist my objectives are many and vary with the type and kind of work.

I would hope that my audience is at least engaged and partly seduced by the work in question. It should if possible have a harmony of form, content and beauty and be able to communicate with viewers cross culturally.

I would hope that my work in images would add some added dimension to the infinite multiplicity of creativity that is the human imagination. Like a good novel or short story, a memorable bit of poetry, or some favorite music.

D&B: What’s your dream photography project?

AC: An elaborate and detailed monograph/book about all of my art.

D&B: What’s the biggest (life) lesson you’ve learned through photography?

AC: I don’t know or think that this is necessarily the biggest lesson I have learned from photography, but I have observed that many photographers, specifically those with an intent to be recognized for their photographs being considered art tend to not challenge themselves or advance their work if their work is praised and recognized for its mediocrity and banality. The tendency is to buy into an inflated hype about the meaning and symbolism of their work when that work is frequently empty, vacant of meaning or purpose.

This crisis of meaning is pervasive throughout the visual arts, but it is very evident in a type of photography of banality that has come to be plaguing the field. Examples of this type of work can be seen in the work of William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, Nan Goldin, Phillip Lorca DiCorcia, just about all the contemporary German photographers, including Wolfgang Tillsman, Bernd & Hilda Becher, and back to the Americans Robert Adams, Garry Winnogrand, Lee Friedlander, the list stretches like some hopeless pandemic circling the planet destroying meaning and narrative, leaving us with nothing more than bland, boring frames that are now supposed to act as templates with which we must input and extract meaning.

The system of art is in the hands of boring, talentless technocrats and administrators who have never experienced art through the act of trying to make it, but have the power to determine the aesthetic choice of art that is ultimately exposed to the world and to history while the world over artists continue to create, mindful of how this most wondrous of human traits have become corrupted. Like everything else in this world art has become corporatized.

It is at their whims and biases that art is understood or more accurately, how art is confused. Photographers like many other types of artists are being conditioned to believe that unique, personal vision is no longer necessary to be an artist and that all is essential is a system of artspeak or criticism that no longer values the merits of the content of images and objects but hell bent on critical hype, that tends to speak volumes about style but states almost nothing about substance or content.

DISCOVER MORE TALENT

See all photographer interviews on Dodge & Burn.

STAY IN TOUCH

Get updates on new photographer interviews plus news on contests, art shows and informed commentary on what’s happening with diversity in photography. Subscribe to Dodge & Burn Photography Blog: Diversity in Photography by Email

Follow me on Twitter @mestrich for more on photography

You must be logged in to post a comment.

+ There are no comments

Add yours