Interview: Honoring Black Motherhood in the Brazilian Slave Trade

The following is an interview with artists Isabel Löfgren and Patricia Gouvêa, creators of the Mae Preta (Black Mother) exhibition which opened in 2016 at the Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos Galeria Pretos Novos de Arte Contemporânea in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

First, before we talk about the exhibition, I’d like to inquire about the current state of Black feminism in Brazil. Are you witnessing a (new) movement?

Black feminism in Brazil has been active for decades, with feminist theorists such as Lélia Gonzalez and Suely Carneiro breaking new grounds within the academy and inside political movements. But one can say that in recent years and with the advent of the Internet, Black feminism in Brazil has blossomed and is becoming stronger and stronger, especially as more and more Black women are entering the universities and becoming historians, novelists, researchers, professionals. Here you can find a timeline and a description of Black feminism in Brazil in Portuguese.

Outside the academy, the movement is very strong, especially in performance, literature, dance and the visual arts. The Internet is a great way of creating community, and there are many blogs and Youtube channels by Black women, speaking to Black women and empowering Black women. This creates a kind of renaissance of Black women’s forms of public expression seeking to create more visibility to a group that is marginalized in society. Black women are most often victims of rape, suffer domestic and institutional violence, and often end up as single mothers in Brazilian society. Together with Black young men, they are a particularly vulnerable group.

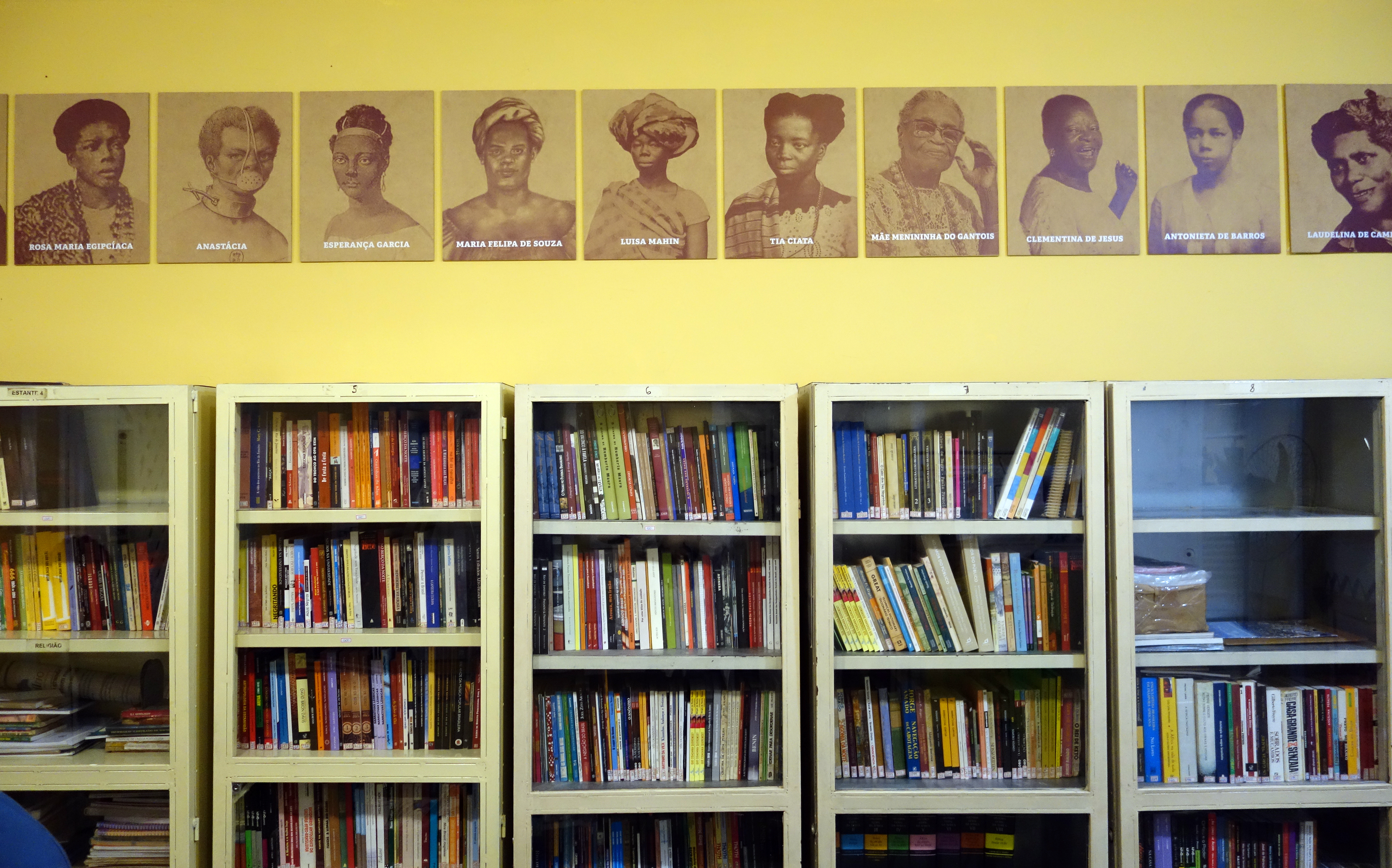

Black Heroine Mural, digital prints on MDF, 30x45cm, 2016. A series of 16 portraits of Black heroines in Brazilian history, from the 17th to the 20th century, permanently installed at the library of the Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos. Photo credit: André Ostetto Motta.

Much of the activism is about maintaining basic civil rights such as the right to legal abortion, education, anti-discrimination, anti-sexism and anti-rape, etc… There is much work to be done because Brazilian society very often does not consider itself racist. It is the Black women and the movements from the periphery that are making this public, and the strategies used by activists, performers, and etc. are extremely creative and powerful.

Naturally, Afro-Brazilian feminism is greatly inspired by Black feminists in the US, and there is no shortage of citations of Audrey Lorde, bell hooks, Angela Davis, and other thinkers of race and gender who reverberate strongly in Brazil today. There are groups of Black female academics pushing the boundaries of the academy to rewrite history in their own terms, and get the Black community out of invisibility, such as the group Acadêmicas Negras at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. During FLIP (International Literature Festival of Paraty), the most prestigious literature festival this year, this group became very vocal because there were no Black authors represented, let alone female Black authors, despite the fact that we have excellent Black women authors doing incredible work and in a year where gender and race issues have been so important in Brazil. Their work is of course pioneering since they have to fight for their space even within the academy.

Ways of Speaking and Listening, double-channel video, 27’27”, 2016. In partnership with Mats Hjelm. Still image with Jessica Castro (left) and Nídia Mara Santos (right).

We have mostly been in touch with Black women who are members of the same Facebook motherhood group we are participating in since our children were born 3 years ago. This group is considered quite radical in Brazil, and we discuss natural birth in a country where C-sections are normative, where abortion rights are limited, racism, and other issues related to motherhood, children and society. In the beginning of 2016, heated discussions about race and motherhood broke out in the group causing most of the Black mothers to create their own separate group. Luckily, we had already started working for the exhibition, and the discussions inspired us to create a video about these discussions with testimonies with the most vocal women in the group. This is where we met Glauce Pimenta Rosa who is an activist and advocate of Afro-Brazilian culture and women’s rights. Through her, we learned about how Black feminist groups are organized and she also introduced us to other women who are the fighters of the everyday and transmit a sense of pride of “negritude” (“blackness”) to their children and their communities.

This community and these debates inspired the video piece “Ways of Speaking and Listening” which is a metaphor for this kind of emancipatory speech where we alternate between speaking and listening as each of seven Black mothers give their testimonies about their own life experiences in response to simple questions like; “what does it mean to be a black mother today?” “ who listens when a Black woman cries?” We even asked them to sing a lullaby for the film. It’s a very powerful piece and it was a wonderful opportunity to let the voices of Black mothers reverberate through the entire space of the exhibition.

Please tell us about the location of the exhibit and its significance.

The exhibition was held at the Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos (IPN), or the Institute of the New Blacks, in the colonial downtown of Rio de Janeiro. It is a memorial site for slavery and houses the archaeological remains of a slave cemetery, a small research library and a contemporary art gallery.

Exhibition view of left wall with Ways of Seeing series (left), Ways of Dwelling (center), and Vênus da Gamboa (right).

To understand the significance of this particular site, it’s important to know a little bit more about some recent events in Rio de Janeiro’s urban history and how it connects to the memory of slavery, which is a relatively new phenomenon in a country with such a significant slave past as Brazil.

In recent years, the city of Rio has made a big effort to remember its slave past after more than a century in oblivion, or let’s say, historical denial, and this happened almost by accident. In 2009, the remains of the Valongo quay in central Rio, where more than one million enslaved Africans disembarked in the 19th century alone, was discovered almost by accident during excavation works to built the new tram tracks for the Olympics. The discovery was so great that it was impossible to ignore. So the city decided to create an archeological site at the quay that connected it to other landmarks of slavery in the area. You can read more about it in an article Isabel wrote this year, Permission to Remember: The Wonderful Harbor and the Tourism of Pain.

Many people don’t realize this, but Rio de Janeiro was once the largest slave port in the world. Just to get an idea, only between 1799 and 1840 more than one million enslaved Africans landed on its shores. If we look at the numbers, Brazil alone received more than 60% of all enslaved Africans sent to the Americas during the entire African slave trade since the mid-1500s, and was the last to abolish slavery in the continent in 1888. In 1800 the Afro-descendant population in Rio de Janeiro outnumbered the white colonial society 3 to 1 – read more about this in our exhibition catalogue in the text by Alex Castro.

Ways of Revealing, Intervention on deteriorated negative by Marc Ferrez, 2016. Based on “Negras,” c. 1884, Salvador – BA, Marc Ferrez/ Gilberto Ferrez Collection/Instituto Moreira Salles.

While most of the enslaved survived the Atlantic crossing from the coasts of Angola and West Africa despite terrible conditions, about 5-10% of each cargo perished upon arrival or shortly after. These bodies were sent to a slave cemetery a few hundred meters from the wharf. This cemetery was very precarious and the bodies were buried in mass graves, then burned and crushed to give way to more bodies. The bodies often came with none or insufficient identification, let alone proper burial rituals. The cemetery, today in the form of a house built over its archaeological remains and the memorial site, was the location for our exhibition.

In the memorial site, one notices that many objects were found. Objects that have been identified by historians and archaeologists as traces of Bantu customs, which indicates that they had not yet been fully Christianized. This means that somehow their souls are still longing for the lands of their ancestors. For this reason, this site has special significance to the Black communities as it marks a very close connection to the motherland Africa.

It is important to note that it is very difficult to trace the exact ancestry for many Afro-descendants in Brazil, and therefore it becomes even more important to establish this link with the history before enslavement. The cemetery offers the understanding that the people who are lying there were born free. It is a site for remembrance and a connection to a dimension of existence that is not determined by slavery. Of course, this is very much a point of debate in the community, we can only say here what is considered significant about the site.

Wall facing the Black Heroine Mural in the library of the Instituto de Pretos Novos. On the foreground, reference photographs from the Instituto Moreira Salles used in the exhibition. On the background, a stencil graffiti art of a famous photograph of an enslaved man. Photo credit: André Ostetto Motta.

There is something very interesting about the discovery of this place which happens one decade before the official discovery of the wharf we mentioned above. The location of this slave cemetery was completely unknown until it was discovered in 1996 under the floor of a house owned by the couple Merced and Petrucio Guimarães in Rio’s port area, in a neighborhood called Gamboa. As it turns out, the cemetery had been landfilled to give way to a new urban development for the bourgeoisie in the end of the 19th century and the traces of the slave past slowly erased. It was only by chance that Merced found the archaeological remains of the cemetery when she was going to renovate her house. She decided to create an institution to honor the memory of the New Blacks, as the Portuguese called those Africans who had recently arrived from Africa.

Since then, the institution has been struggling to keep afloat with very little support, having been basically ignored by the city until the Olympics when the whole area got a boost because it was strategically located in the center of town. Since 2009, the Brazilian curator Marco Antonio Teobaldo created a contemporary art gallery on the site where he shows artists and projects that refer to Afro-Brazilian memory, history and culture. We were very happy to be invited to show and have the ability to present our research. We decided to create an exhibition with the main theme of the memory of slavery through aspects of motherhood with a feminist perspective, to honor the women and children buried there and to address the history of Black women in Brazil.

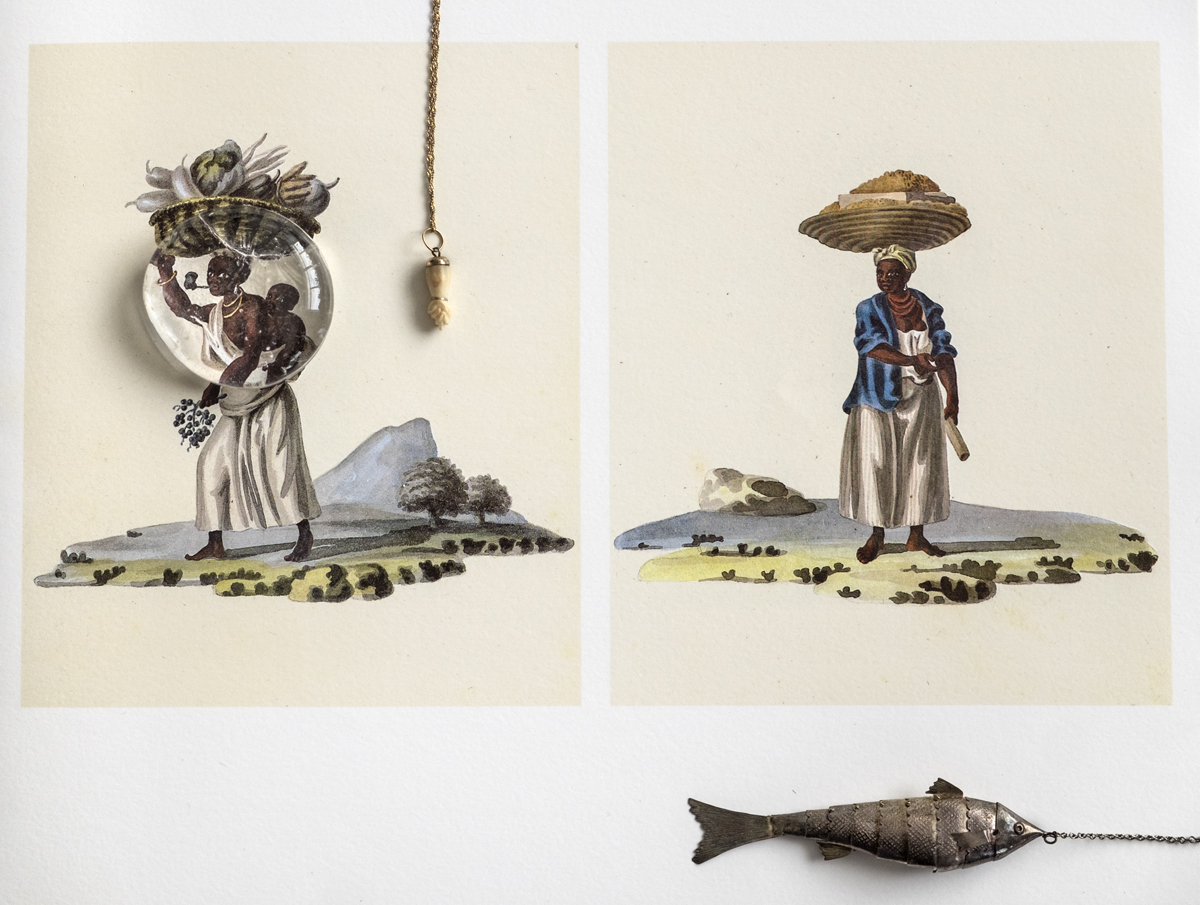

Ways of Seeing, Interference on print by Johann Moritz Rugendas, photographic print, 30x40cm, 2016. Source image “Negras do Rio de Janeiro,” in “Voyage Pittoresque dans le Brésil,” by J.M.Rugendas, 1835.

Where did you begin your initial research and how long did the exhibition planning and design take to complete?

We began this research in 2015 when we participated in a small group show called Crossover in a gallery in a part of downtown Rio that still has many colonial buildings. Our joint artistic method is to begin our investigations in direct response to the site. Curiously enough, we found a copy of a famous print from colonial times on the door of the gallery. The image depicted an enslaved woman carrying her baby wrapped on her back with a piece of fabric, like many women still do in Africa. We then set out to find out everything we could about this image, who had painted the copy on this door and why, what was the original image, who had painted it and when.

We eventually discovered the author and the title of the original print, and we were intrigued by all these stages of image reproduction that contributes to our understanding and representation of that time in Brazilian history. (The painter was J.M.W. Rugendas and the print was called “Negresses of Rio de Janeiro”.) Since the exhibition was called Crossover, we wanted also to re-signify this image by changing a few elements. So we re-enacted the pose by recreating the costumes and we chose a male model to cross-over the boundaries of representing race and motherhood. We then substituted the painting on the gallery door with photographs of the model with the same poses.

Entrance to the exhibition Māe Preta. Instituto de Pesquisa e Memória Pretos Novos, Galeria Pretos Novos de Arte Contemporânea, July 2016. Photo credit: André Ostetto Motta.

Besides working with the site, another part of our working method is to work with contemporary interpretations of archival images and to confront them with the present. In a previous exhibition, we used interviews with locals as a method to gather stories about the site we were working on. This time, we would repeat the idea of interviews, but not directly related to the site. We would interview women who are connected to movements that question the condition of motherhood – Black motherhood – and offer different points of view of a considerably fragile group in Brazilian society. Watch our video Ways of Speaking and Listening.

In the beginning of 2016, we got funding for a solo exhibition, Mãe Preta, and were invited to do it at the Instituto Pretos Novos Contemporary Art Gallery which we described above. It was the perfect opportunity to continue this line of research. But this time, we were literally entering sacred ground, because the gallery was located inside an archaeological site which is the cemetery. So we decided to take this aspect very seriously and started connecting the archives with important symbols of Afro-Brazilian culture, and relating them to this specific site. Our exhibition is entirely site-specific – the way we placed the elements in the gallery, and even included an intervention in the Instituto Pretos Novos library. It was nice because this is how we have always worked together – connecting historical sites to archives and personal experiences of both.

We created, produced and executed the entire show from scratch in six months, most of it long distance since we live in different time zones (Patricia in Rio and Isabel in Stockholm). It was crazy, but we even managed to cast, film, edit and produce a 27 minute video in that period. Editing the film took one entire month. It was hard work! I believe we must have exchanged dozens of WhatsApp messages everyday for all these months, it was a real push.

What kind of financial and institutional support did you receive for this exhibition?

We got the financial support of the city of Rio de Janeiro for a special line of financing for cultural events during the Olympics officially called “Edital Fomento da Secretaria de Cultura da Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro” which was a unique opportunity. This special support was a way for the city to highlight the urban renewal they did in Rio’s decadent port area and attract tourists and locals to see the “new” town. It was interesting that the street where the gallery is located was not even ready when we opened the show, so we were pretty much working in front of a construction site. We also had the support from the Swedish Arts Grants Committee and other local partners and suppliers.

We had of course the institutional support of Instituto Pretos Novos who allowed us to create an artistic intervention beyond the gallery and into their library, and the generous support of their staff. We also negotiated a partnership with Instituto Moreira Salles, one of the most complete photography archives in Brazil, and who kindly granted us high-resolution files for most of our photo-montages based on material from their archives.

Where did you source the archival images/engravings from?

According to the art historian Marcus Wood, Brazil has one of the largest slavery image archives in the world, and most of it is preserved in the country itself. We worked together with the National Library (Biblioteca Nacional) to acquire old newspaper articles containing ads for wet nurses, which was one of our main interests. We scoured through nearly 90 years of newspaper ads, from the 1810s to the turn of the century.

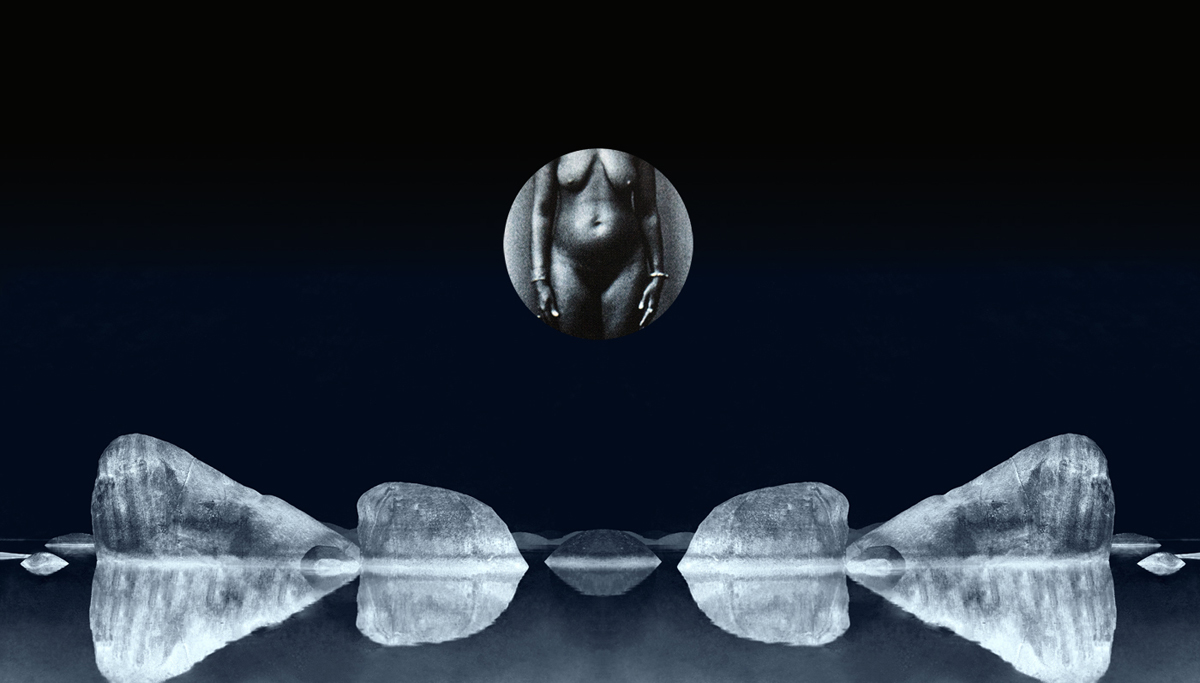

Ways of Dwelling. Photographic print, 120x75cm, 2016. Photomontage with image of pregnant woman from August Stahl ca. 1880, and Marc Ferrez, “Baía de Guanabara, Paquetá” ca. 1885, Gilberto Ferrez Collection/Instituto Moreira Salles

In terms of images, we partnered with Instituto Moreira Salles and their incredible collection of 19th century photography in Rio de Janeiro. There we could find the most iconic photographs/daguerreotypes made by famous photographers such as Marc Ferrez, Georges Leuzinger and Victor Frond. In terms of paintings and prints, there are enough museums with original works in Rio de Janeiro, but since we were doing interventions directly on prints, we worked mainly with reproductions of paintings and prints from books.

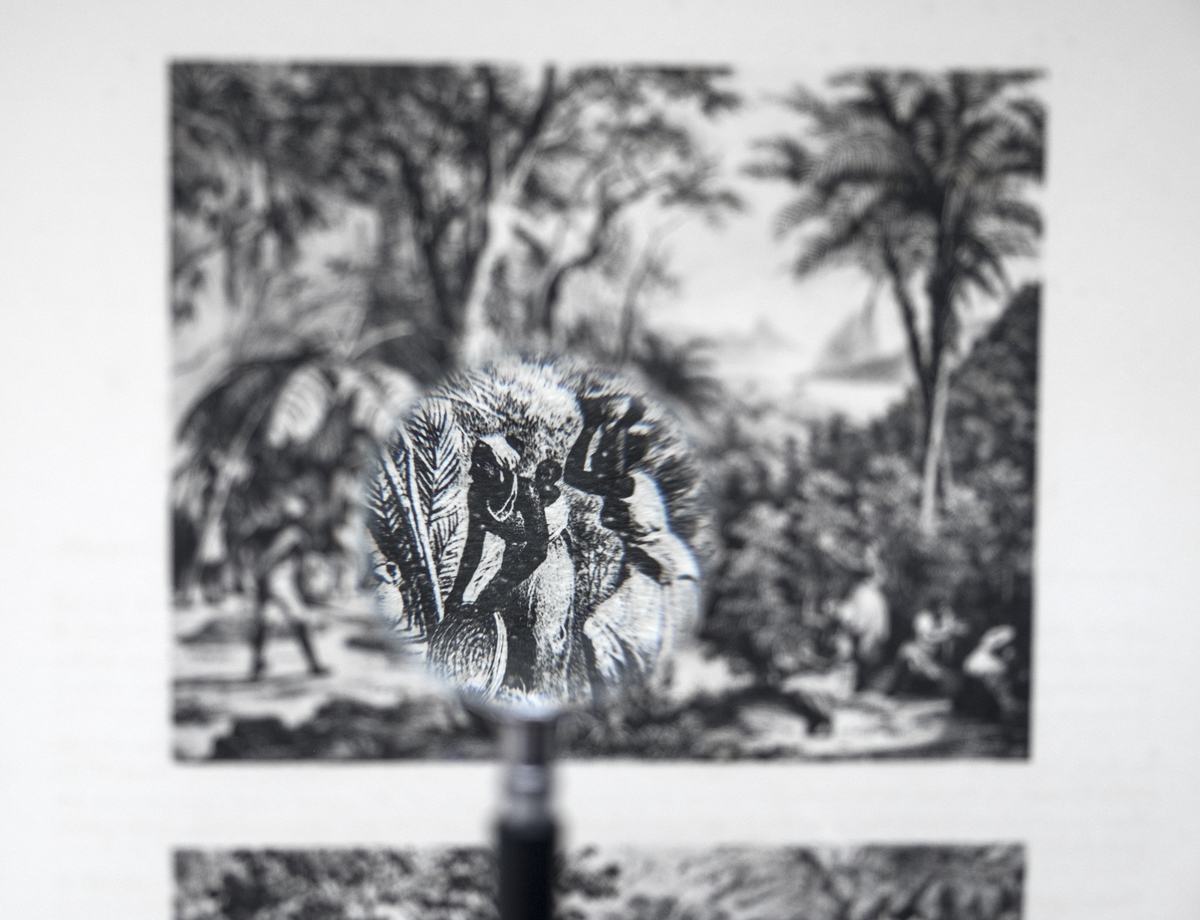

What’s the symbolism behind the magnifying glass and other objects used in your photographic interventions?

We used several objects in the “Ways of Seeing” series. The magnifying glass is an object we have used continuously in our joint work and is a visual metaphor for taking a closer look, mimicking the gaze of the researcher that looks for fine detail and hidden elements in an image. It is a metaphor for the scientific method of analysis, as if looking for evidence. We also used glass lenses and glass prisms that distort and break the light and were also used to highlight details.

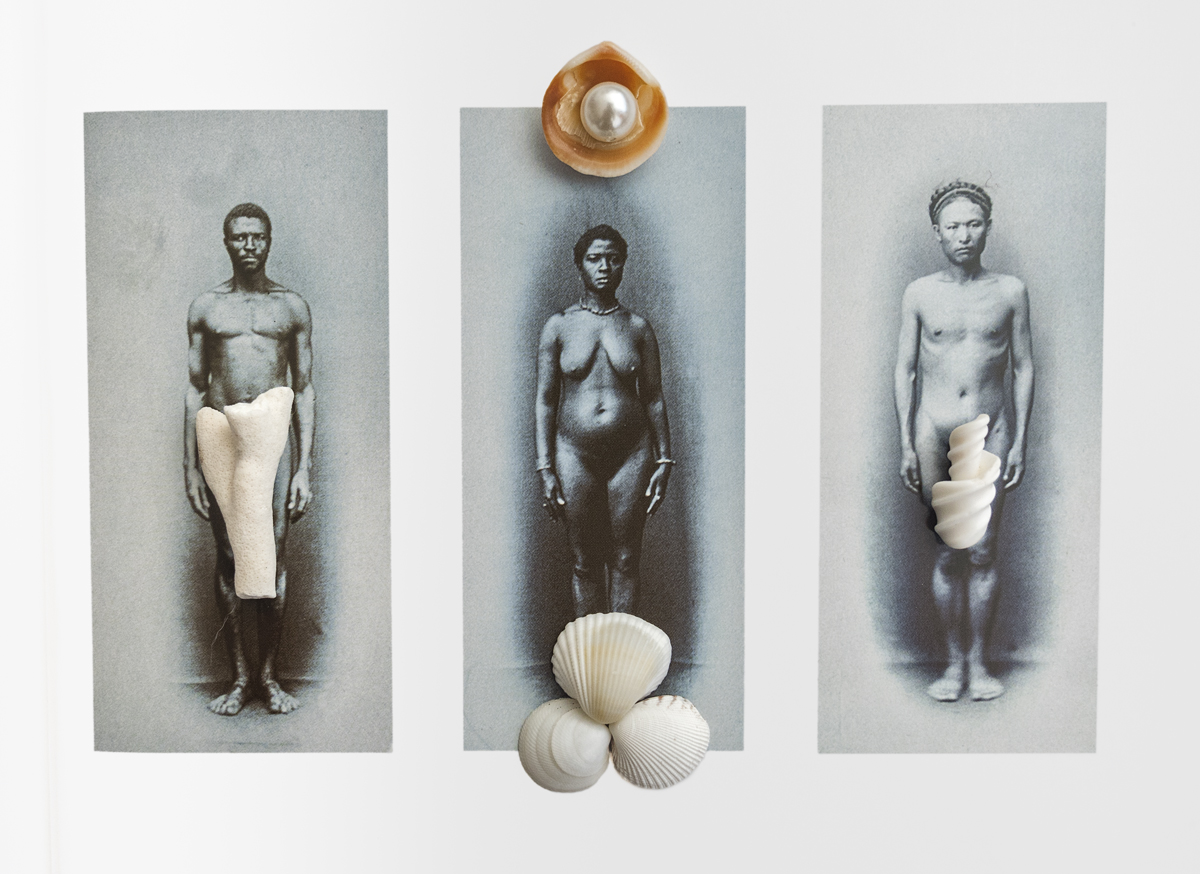

The pearls, seashells and corals are generally connected to the sea goddess (orixá meaning deity or goddess in the Afro-Brazilian pantheon) Iemanjá/Yemaya. We designated one of the very few images of pregnant women as a Venus springing from shells and pearls as a possible image for an Afro-Brazilian Venus, the Venus of Gamboa, which is the name of the neighborhood where the gallery is located.

Vênus da Gamboa, photographic print, 50x70cm. Intervention with objects on reproductions of photographs by August Stahl, ca. 1885.

The sea is very important in this sacred space for several reasons. First, the persons buried in the cemetery mostly arrived straight from the sea. The sea in Bantu cosmology, also known as Kalunga, was considered to be the site of the ancestors. In fact, one of the myths passed on through generations was that when they boarded the ships in Africa, they thought they would meet the ancestors on the other side of the sea. The sad part is that since many of the bodies never received proper burial rituals, their souls are considered to be floating until they can reunite with the ancestors.

The cemetery was also located very close to the harbor, and by looking at old maps, we figured out that the cemetery was located only one hundred meters away from the beach which is now landfilled. We even used a 19th century photograph of the area in one of the pieces to highlight this. Archival photographs of water, the area and of one of the very few photographs of pregnant women we found in the Agassiz/August Stahl archive can be seen here. These works were hung on the wall of the gallery which was nearest the old coastline. Each orixá has a designated color, and each devotee wears a bead necklace with that color. We chose the yellow bead necklace of the orixá Oxum – the deity of rivers and waterfalls, and also goddess of fertility and motherhood – to highlight certain features in some images.

The curator Marco Antonio Teobaldo is also a collector of images and objects related to Afro-Brazilian heritage. He owned a silver pin shaped like a fish that supposedly belonged to an enslaved woman and is a symbol of freedom. The fish and other silver jewels were like amulets that together formed a string of pendants called balangandã (ba-lan-gan-dan). After a number of years, a woman would have amassed enough silver jewels to buy her freedom. In the photography archives, we often ran across richly adorned images of Black women and some wet nurses with children, many of them showing off their balangandãs as a symbol of status.

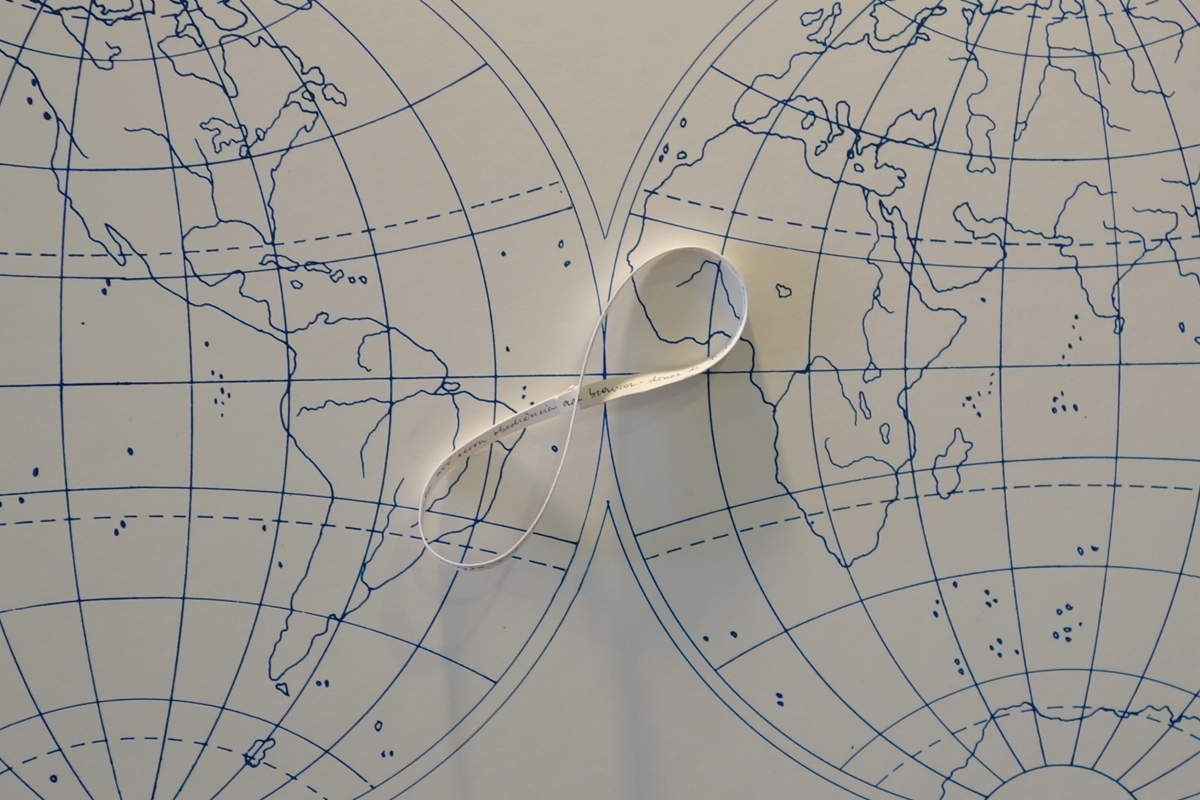

We also used the möbius strip, which for us is a symbol of the eternal return and keeps coming back in our work. In “Ways of Navigating” we place a möbius strip with a poem written inside connecting Brazil to West Africa as a symbol of the inextricable connections between both continents that even fit into each other only separated by the ocean. Again, water is extremely symbolic here as it is what has carried Africans to Brazil and is what also carries them back to the lands of their ancestors. We use also water as a symbol of healing of all the violence and sadness involved in this theme.

Ways of Navigating, collage on paper, 50x70cm, 2016. The strip of paper connecting Brazil and Africa contains a verse from a poem by Brazilian writer Conceição Evaristo, “Voices-Women” from 1990.

Were there any particular narratives from the slave mothers that stood out to you?

Like in America, the Nanna is a very important and pivotal character in the formation of society. It is through the Black women’s breast milk that fed all their master’s children, and sometimes their own. Wet nurses were considered valued commodities in the slave domestic economy, and since they were so close to the families of their owners, they had quite high status among the enslaved. In fact, the portraits of wet nurses holding their white babies is quite common. However, these photographs were not meant to depict the wet nurse individually – they were meant to record the child who could only sit calmly in the lap of her nanna.

Of course, families took care to make the wet nurses look like prized properties and many of them appear wearing fancy clothes. The variety of clothing and garments, which were sometimes entirely African with printed textiles and turbans, is incredible to analyze. However, even though the wet nurses appear everywhere, these women are hardly ever the protagonists of the picture. In fact, the wet nurses take an entirely secondary role even pictorially – they are supposed to be part of the background whose function is to hold and calm the child. Their names are rarely recorded on the photographs.

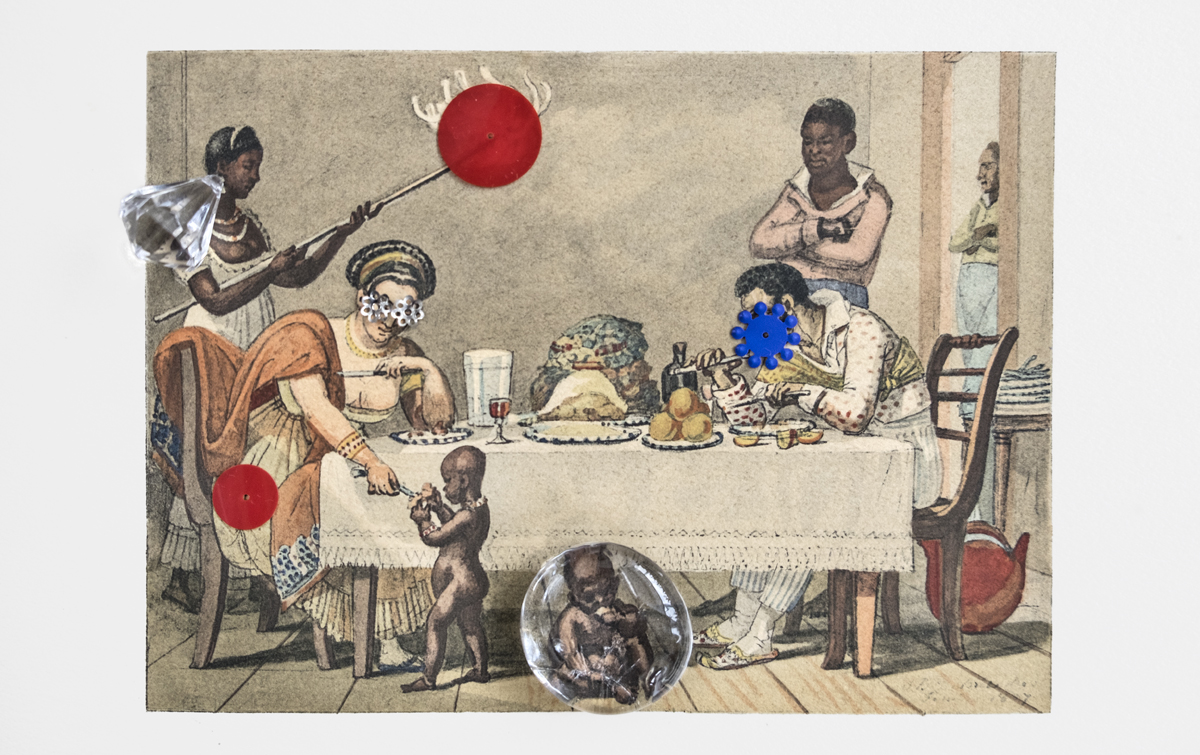

Ways of Seeing, interference on print by Jean-Baptiste Debret, photographic print, 24x30cm, 2016. Reproduction of print first issued in “Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil,” by Jean-Baptiste Debret, Paris, Firmin Didot Frères, 1834-39.

Unfortunately, we still see this relationship in a more modern form in contemporary Brazil. What we wanted to do is to challenge this image of the wet nurse or of the “black mother” as someone who is taken for granted in society. By highlighting the Black Mothers in the archival images, we wanted to make them protagonists of the images, as well as trying to give them agency. While we were very much inspired by these images, in the series “Ways of Seeing” we chose to use images where the wet nurses and black mothers were somehow a part of larger groups or in the background. What we wanted to do was to literally bring them to the foreground from a mass of anonymity.

We were also interested in their own feelings of motherhood, and the excruciating pain of having to separate from their own children in order to care for the children of others. This is less written about than the extensive analysis of domestic work and wet nursing. By reading hundreds of newspapers ads announcing the services of wet nurses through several decades in the 19th century, we noticed that most of the ads announced women with “good milk” but no children. So what happened to their own children?

Ways of Seeing, interference on reproduction of print by Jean-Baptiste Debret, photographic print, 50x70cm, 2016. Reproduction of print “Litière pour voyager dans l’intérieur des terres” (Sedan to travel to the countryside), in “Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil,” by Jean-Baptiste Debret, Paris, Firmin Didot Frères, 1834-39.

Sometimes the ads would say that their children had died of fever, but most said nothing. If we think that by that time the milk provided by a mother (or a wet nurse) was the only way to guarantee the survival of a child, we can have an idea of the extreme pain of separation these enslaved women must have suffered – to the point of madness, perhaps. We started looking for the destiny of these hundred and thousands of abandoned children. We found a report from 1838 with statistics and information about the construction of an orphanage in Rio. We printed out the page and put it in the exhibition, with a magnifying glass so the reader can look closer.

We did not stress the issues related to labor, which would connect the wet nurses to the nannies of today. This is a topic that has been well explored in other formats, films, documentaries, literature. We wanted to focus on the issue of maternity, the relationship to the child and the power structures that obliged the Black Mother to be a cornerstone of the white family, but to falter in raising and keeping their own families.

Ways of Seeing, interference on image by Marc Ferrez, photographic print, 30x40cm, 2016. Source image: Marc Ferrez c.1885. “Partida para a colheita do café, Vale do Paraíba,” Gilberto Ferrez Collection/Instituto Moreira Salles.

What kind of feedback have you gotten from the local community and the Brazilian community at large?

Despite all the problems with accessibility to our exhibition site in Rio de Janeiro (the street where IPN is located was still blocked for regular traffic due to the construction of a new tram line – which has not yet been concluded even several months after the end of the Olympics) almost 2.000 people visited the exhibition in 2 months, including many school and University students, artists, historians, locals, tourists and Olympic delegations.

Three important online sites related to Black culture and Black resistance in Brazil published articles about our research and this was very important for us because it somehow legitimated our project inside the Afro-Brazilian communities. I believe that we have got very little criticism in terms of our artistic content, which we are happy about. I guess it was because the work was solemn and quite understated. We did get some criticism about our own positioning in relation to the project, as to why we were doing it, why should we touch on these themes… We do this because we are citizens of an unjust society and working with bringing awareness to these histories, especially in a place like IPN that is also a centre for research on these topics.

Ways of Seeing, interference on image by Marc Ferrez, photographic print, 30x40cm, 2016. Source image: Marc Ferrez c.1885. “Partida para a colheita do café com carro de boi, Vale do Paraíba” Gilberto Ferrez Collection/Instituto Moreira Salles

With this in mind, we did an intervention on the Institute’s library with three components: first, we asked for donations of books written by Black female authors and academics to enrich the collection and bring the intellectual work of Black women in Brazil to the fore, secondly, we created a meta-category called “mãe preta” in the existing collection to bookmark the works by Black female authors or related topics (there were about 50 titles in a collection of 1,000 books); and third, we created a portrait gallery of Afro-Brazilian heroines in the library which remains there as a way to bring visibility to the lives of Black women’s resistance in Brazilian history.

We have been in touch with researchers in universities and we have so far participated in a couple of conferences, especially in feminist events. We have been contacted by several interested parties in the past months who are interested in showing the works, and we are waiting to see how and when we will do this. However, the best reception we could ever get was the participation of all the Black mothers in the film who trusted us to carry their voices forward and believed in the project. Without their support, it would not have been possible to do this project.

Ways of Seeing, interference on print by Jean-Baptiste Debret, photographic print, 30x40cm, 2016. Reproduction of print first issued in “Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil,” by Jean-Baptiste Debret, Paris, Firmin Didot Frères, 1834-39.

How will the project evolve, if at all? Will this be a traveling exhibit?

Recently we were awarded important prize, the Funarte Conexão Circulação Artes Visuais, given by the Brazilian National Arts Foundation. It’s a prize for the production of two exhibitions in Brazil next year which will give us the opportunity to tour the exhibition and add new works in response to two new cities with each their own legacy of slavery. Our desire is to always try to make the research relevant locally. In each city we are going to research about the memory of the slavery, the histories that were not really told and the imaginary maps to make new pieces to be shown in the exhibitions.

With this prize it will be possible to show the exhibition at Galeria Funarte, in São Paulo which is an institutional, more “white cube” kind of space. After that, we will show in another city in the north of Brazil, São Luis do Maranhão, which has a very strong history of Black female resistance since the colonial times. For example, in São Luís, Nã Agotimé was a queen from the old kingdom of Daomé (known today as Benin, in West Africa) and was captured and sold as a slave and sent to Brazil, where she introduced the cult of the voduns in São Luís and founded the Casa das Minas in the 19th century. This queen will definitely join our portrait gallery of Afro-Brazilian heroines, like the one we initiated at the Instituto Pretos Novos library. It’s a small contribution to the idea of rewriting history on women’s terms, putting the narratives of women forward so that they can become ever more visible. Knowledge is everything!

Ways of Seeing, Interference on print by Johann Moritz Rugendas, photographic print, 90x104cm, 2016. Source image from “Voyage Pittoresque dans le Brésil,” by J.M.Rugendas, 1835.

Do you think the significance of the Mãe Preta exhibition can transcend the boundaries of Brazil?

Yes! We are very interested in tracing the relations, testimonies and the memory of the wet nurses and female resistance during the slave period in Latin America and the Caribbean, and also in the US, a country that has a similar history but with interesting differences in the aftermath of slavery. Afro-Brazilian feminism is very much influenced by African-American feminism and there is definitely a voice that resounds throughout the entire continent.

It would be very interesting to see the reaction to this exhibit in Cuba as it is a country that shares many similarities with Brazil in terms of Black culture, ethnicity and religion. Even if our exhibition responds to a Brazilian context, we believe that bringing awareness to the plight of mothers who find themselves in marginalized conditions may resonate elsewhere. We have to try and see what happens. So far, we have only showed the film once in Sweden, and a gender studies professor expressed some interest in using the film as part of a university course on race and gender.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

+ There are no comments

Add yours